Anyway.

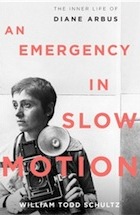

On a completely unrelated note, Diane Arbus is creepy. I'm reading about her in this book:

She's weird and her pictures make me feel bad about myself and the world, kind of like Radiohead. In any case, I have her pictures taped to the wall above my writing desk.

This thing below is one half of a review I wrote for MTLS, where I look at two short story collections. You can find the entire review here.

The Divinity Gene

by Matthew J. Trafford

Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 2011

192 pp. $22.95

Distillery Songs

by Mike Spry

London, ON: Insomniac Press, 2011

160 pp. $19.95

In her stint as guest-judge for The Giller Prize, British writer Victoria Glendinning railed against Canadian literature for being too boring, too regional, too . . . Canadian. In her eyes, we Canucks lack imagination, a willingness to take risks. See, for example, this excerpt from a piece in The Globe:

It seems in Canada that you only have to write a novel to get grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and from your provincial Arts Council, who are also thanked. Complaints were once voiced that most shortlisted Giller novels emanated from just three big-name publishers, all owned by Bertelsmann, and that virtually every winner lived in the Toronto area. Now, many of the submitted authors, and their rugged subject matter, hail from Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland. That’s maybe because small publishers too are now subsidised, and they proliferate. If you want to get your novel published, be Canadian.

Though one can concede that maybe, just maybe, Ms. Glendinning has a point, it’s also clear she hasn’t read Matthew J. Trafford or Mike Spry. The Divinity Gene, Trafford’s debut collection, is a wicked fusion of Italo Calvino and the kind of funky grist you’d find in McSweeney’s, while Spry’s own debut collection, Distillery Songs, is a welcome knee to the groin of anyone who says that Canadian’s can’t be funny, subversive, or over-the-top.

The stories in The Divinity Gene tend to go one of two ways. Either they’re intensely creative pieces – a dance club run by angels demands of its patrons an odd sort of bartering, the son of a fisherman watches as dad slices open a mermaid – that challenge perception, or more conventionally realist stories where character trumps concept.

While the cover blurbs praise The Divinity Gene’s imagination, this reader found the glitzier pieces at times lacking. Take iFaust, for example. Here a new app for iPhones lets its users sell their souls for material ends. Once our justly-warped minds regain their natural shape, we start to consider the lives in the story. The problem, I suspect, has to do with length, lay-out, and what Trafford chooses to dwell on; (too) much of the story deals with the glamour of the Faustian narrative trajectory, at the cost of actually getting to know the characters.

Another story, “The Grimpils,” offers a plot almost as absurd as the story’s title: the call of a mysterious writer draws friends and family of our main characters to Paris, where, it turns out, they’ve somehow been assimilated into an odd kind of cult. They become, to use Trafford’s term, ‘grimpils,’ a play on the word ‘pilgrim.’

The story never quite transcends its conceit. When Canadian Richard visits the American embassy for answers, his plea for help sounds almost comical. “We’re here to talk to you about a very serious situation,” he explains, and he’s right: if someone close to me flew to Paris, heeding the siren-song of some writer, and became a weird nihilistic fanatic, I’d be concerned, too. But the sense of loss swirling at the story’s core gets lost in what feels like a running joke, while the seemingly superfluous inclusion of footnotes gives the impression that what we’re reading is actually some kind of science experiment.

Again, the story is strongest when Trafford focuses on the emotional cores of his characters and limits the time we spend vacationing in Absurd-istan. The shared grief of Richard and co. is heartbreaking enough to almost transcend the story’s silly conceit, and the ending, I have to admit, arrives with surprising power.

Stronger are more subtle stories like “Thoracic Exam,” which brilliantly uses a medical exam as a narrative frame, and “Forgetting Helen,” where our narrator, who has literally spent his entire life in a library, might have found his Helen of Troy roaming the stacks. In both cases, Trafford never loses sight of what this reader considers the most important part of story-telling: making me care, truly, about the people he’s created.

To my eye, two stories stand out from the others as evidence that Trafford can tell one hell of a story.

“Past Perfect” follows its queer lead as he struggles to comprehend his partner’s descent into dementia. There are no otherworldly creatures, no supernatural occurrences, no blinding pyrotechnics, just a man who loves another man who is dying, their relationship masterfully captured with a subtlety often at odds with the rest of the collection.

Impressively, Trafford manages to do something similar with “The Divinity Gene,” the story that probably first got the author noticed when it appeared in the brilliant Darwin’s Bastards, a collection of Canadian speculative fiction published by the same folks who put out Trafford’s debut.

The conceit isn’t entirely unfamiliar: some intrepid scientist breaks down Jesus’ DNA, spawning an entire race of Christs who behave in weirdly opaque ways. The story takes its time, developing into a surprising meditation on grief, spirituality, and humanity. Surprising, I say, because a lesser writer might milk the Christ-resurrection angle to gimmick proportions. Not Trafford. Once he’s got logistics out of the way, his attention shifts from Godliness to base humanity, where the inner struggles of Maciej, the man who cracks the ‘Divinity Gene,’ force the reader to ask big questions about faith and the capacity to hurt and hurt others.

The story anchors the collection and proves that, when he isn’t playing mad scientist, Trafford can work wondrous, heartfelt alchemy, a skill he shares with Chris Adrian, an American writer known for playfully bending reality. Like Adrian, recently named one of the New Yorker’s best writers under 40, Trafford juggles humour, sadness, and an often delicious sense of the surreal. The result, fictions that play to either mind or heart but rarely both, suggest that Trafford has the potential to become a force in Canada’s literary world. He just needs to slow down and listen to his characters, first and foremost.

[First published in MTLS]